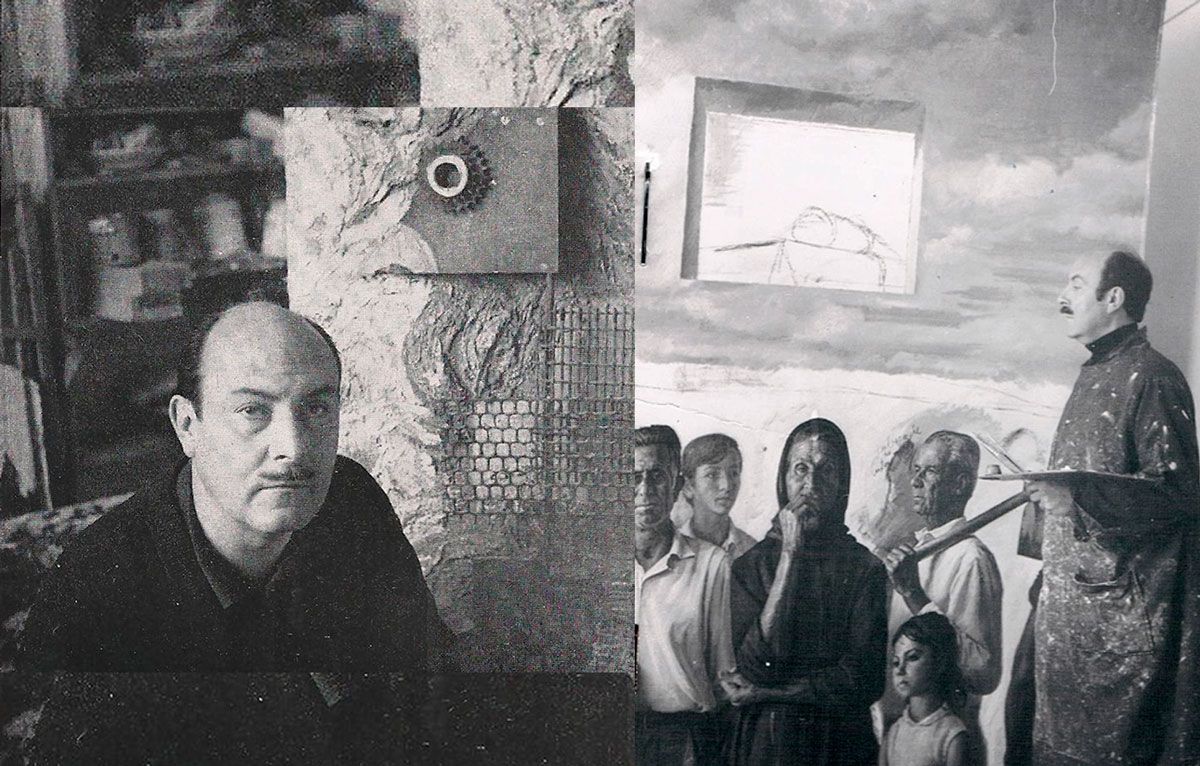

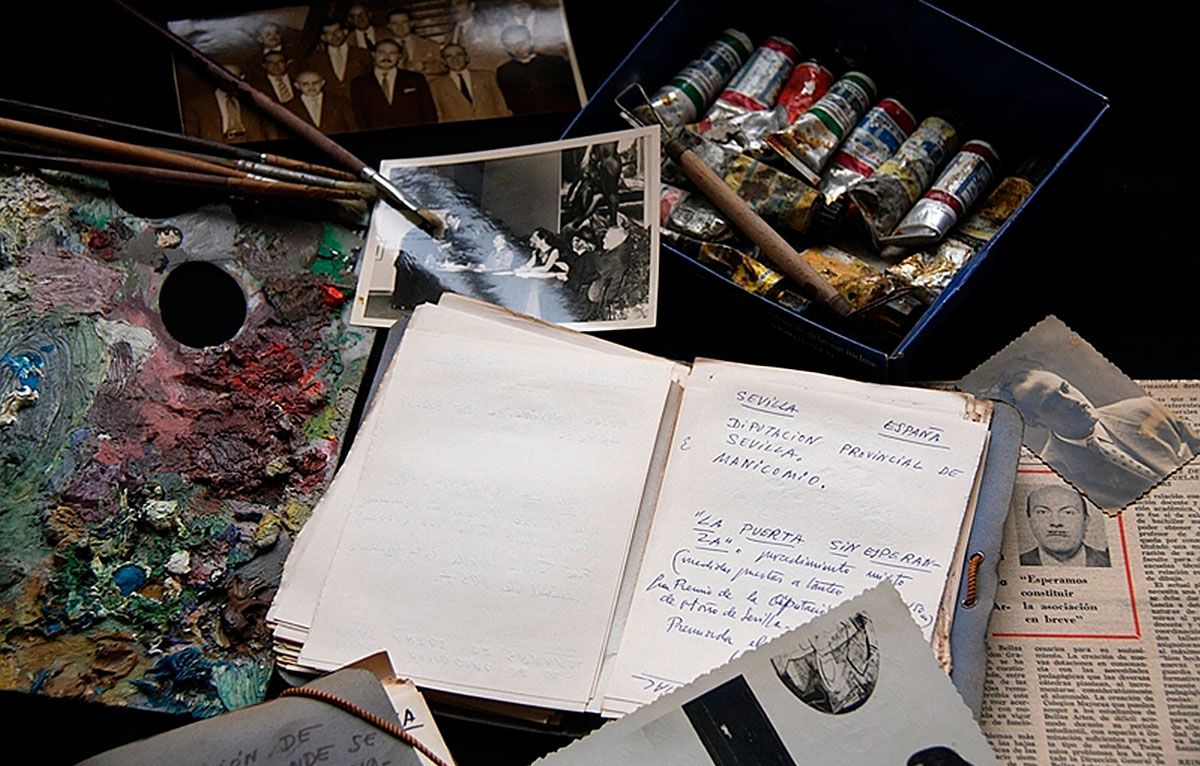

In the work of Amalio, three periods can be distinguished: the first one (1937-1966) is a classic and learning stage of training in drawing that is defined as realistic, with well-valued ranges and bright colors and solidly structured compositions. It is a stage of traditional figuration. In the second one (1966-1986) we can see three aspects that, for some years, were parallel, one -more short- “avant-garde” or rupture, whose beginning coincides with the decade of the sixties -time of social upheaval: the French May of 1968, and in Spain, the first concerns of Franco’s decline; all of which will be reflected in this explosion of the Amalian painting. Here we can integrate the so-called “touch-paintings”, fruit of his search in the field of material expressionism, the later “tarol-armonicismo”, as a way of behaving towards art, and, as a culmination of this tendency, the edition of Reolina (1986), his first visual collection of poems. And a third one (1986 and the following years) that is the last decade of his life, in which we can talk about “the painting and the poetry of silence through silence”. This stage is expressed in Barely with his wound, unpublished collection of poems whose dedicatory echoes the loss of his voice.

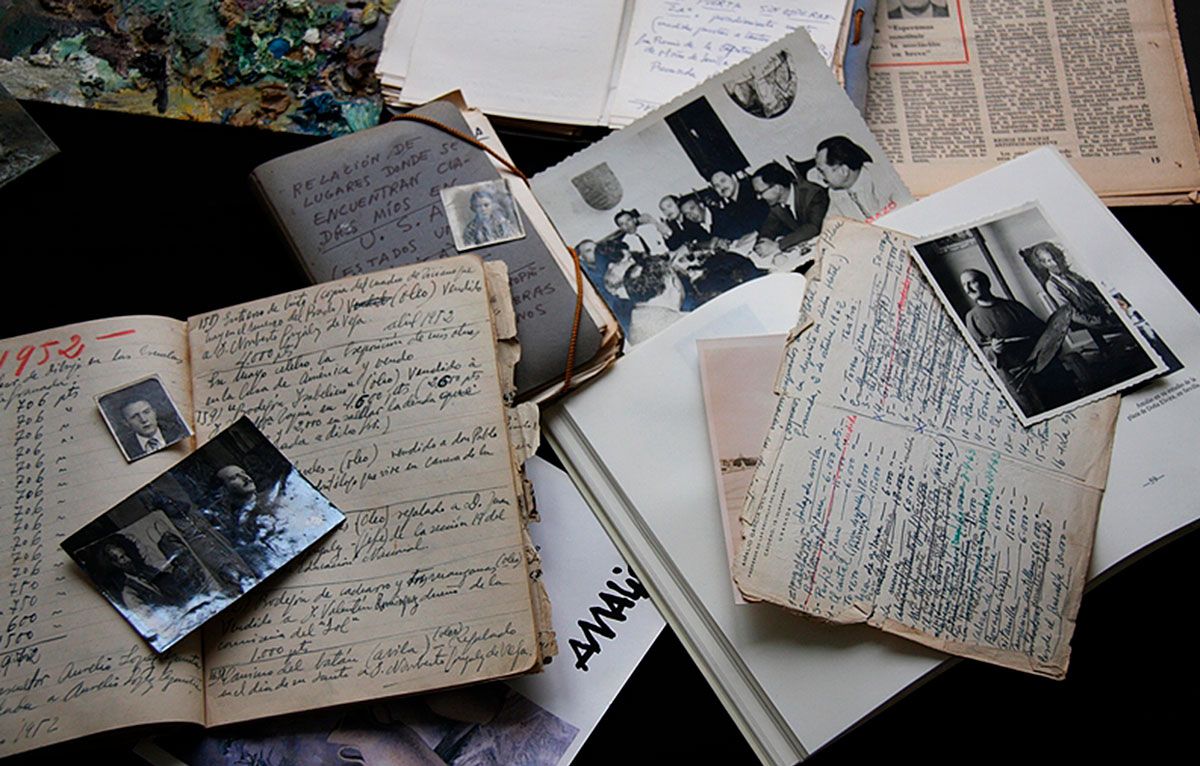

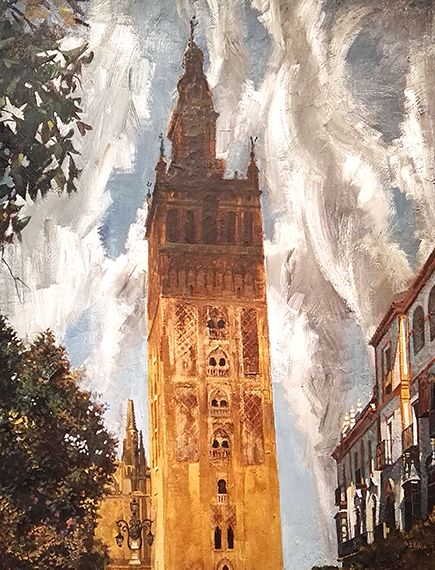

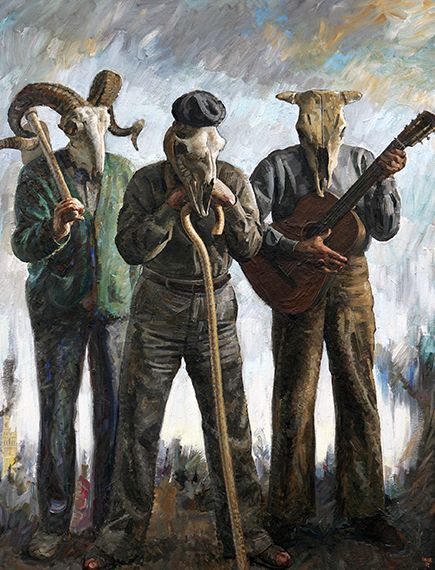

From the 70s forward, Amalio was jealously keeping his Works shielded from the market, while he was bringing out the “365 views of the Giralda tower” series, “The Proletarian Apostleship” and “Esperanza’s world”. This especial purpose for safeguarding his production has had a primary objective of maintaining available some key works to be exhibited today as a testimony and legacy of Andalusian people.

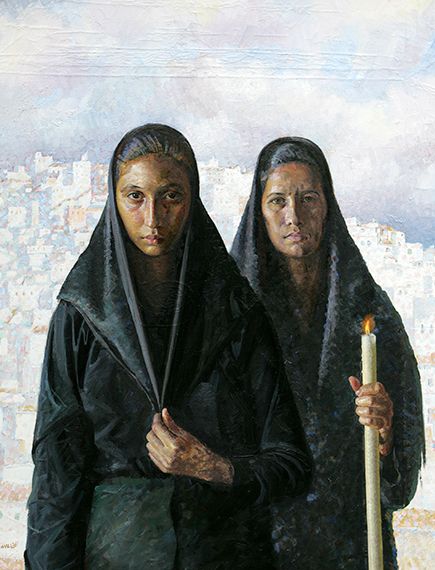

Amalio’s artistic legacy is ahead of his time providing icons and values of the XXI century as it is the women leading role, the social recognition and attention of old people and the underdogs demands. It is about a work that leads the viewer to a symbolic, evocative and critical Spanish world that represents a without-words manifesto of poverty where the realism and lyricism get intermingled and are masterfully superposed.

Amalio highlighted his models qualities in their portraits demonstrating a great respect for their personality without being a judge or a censor. This respect is the result of a moral and aesthetic condition he reached thanks to his humanistic education and to a solid culture that conditioned him in a natural way to not relativize people at the expense of his art. His exquisite art was always subjected to the model person.

Many of Amalio’s paintings are in picture galleries, museums and foreign and national collections, being USA the country that hoards more frames. Most of these paintings belong to his first period in Granada.

One of his master pieces, “El Pan encadenado” (1971) [The chained bread], oil on canvas. 236×200 cm. is now at the Contemporary Art Museum Queen Sophia, in Madrid.

He is not only a multifaceted and plural artist who has left a great production, but someone who belongs to that group of artists that has created a personal universe, his personal world. Amalio positions himself as a universal artist, not only in his paintings but also in his writings.

Amalio, above all is a painter, though he is also a poet and writer as is reflected in his books of poems: “The flowered hand” (1974) [La mano florecida], “The bread in the look” (1977) [El pan en la mirada], “Testament in the light” (1980) [Testamento en la luz], “Alquibla” (1983), “The windmill” (1986) [Reolina] and other books as “Gypsies” (1956) [Gitanos], “The Giralda tower, 800 years of History, Art and Legend” (1987) [La Giralda, 800 años de Historia, Arte y Leyenda], and the stories “Tales and legends of the Giralda tower” (1991) [Cuentos y leyendas de la Giralda]. All of them are the reflection and the intellectual space that shroud his paintings.